Why aren’t we all serverless yet?

The median product engineer should reason about applications as composites of

high-level, functional Lego blocks where technical low-level details are

invisible. Serverless represents just about the ultimate abstraction for this

mindset. Consider AWS

Lambda’s elevator

pitch: “you organize your code into Lambda functions [which run] only when

needed and scale automatically. You only pay for the compute time that you

consume”. Engineers can get away without paying attention to infrastructure,

resource allocation, runtime management, cost optimization, or similar concerns

just like they don’t worry about CPU cache coherency algorithms or the electric

grid .

And yet, despite an appealing value proposition, the industry pivot to

serverless compute as the default architectural pattern for cloud

applications, hasn’t really happened. As AWS Lambda turned

10

last November, Will Larson

posted:

Something I’m still having trouble believing is that complex workflows are

going to move to e.g. AWS Lambda rather than stateless containers orchestrated

by e.g. Amazon EKS. I think 0-1 it makes sense, but operating/scaling

efficiently seems hard. […]

The scepticism seems well justified. In 2023 Datadog

reported serverless

adoption growing between 3-7% among the major cloud providers, with over

50% of their customers using some version of it. However, there is a

long way from “we use lambda” to “our complex workflows are all

serverless”, and the growth rate seems too incremental to make the case

that an exodus is on the way. The general trend of software eating the

world is a simpler

and more reasonable explanation for that level of growth, especially

with AI putting downwards pressure on the cost and cognitive overhead to

generate small pieces of purpose-specific code (a sweet spot for

serverless). Otherwise, the figures don’t really signal a mass

migration.

What are the sources of friction against serverless?

In this piece will discuss two factors. First, fatigue from the last

paradigm shift to microservices (a term I’ll use as shorthand for

architectures based on small, loosely coupled services with bounded

contexts). That transition was much harder than expected because of

immaturity in tooling, infrastructure, but also a critical gap between

technical and organizational readiness. Second that, while some might

consider that the industry is being too conservative, caution is in fact

reasonable because serverless will exacerbate the same type of

challenges that were created by microservices (many of which are still

not fully resolved).

The post-traumatic syndrome of microservices

A technological trend can be directionally correct, but direction says

little about timing, which is where most people get burned. Early

adopters share part of the industry bill for maturing a technology, so

in a way, every migration implies a bet that the cost / benefit ratio

will work out either because the maturity gap is already small enough,

or because the new technology will provide outsized benefits.

Microservices made a canonical example of how easy it is to miscalibrate

that bet. Since the trend started ~15y

ago, these

architectures proved effective to solve real problems of scale,

reliability or productivity. But also showed a heavy reliance on

load-bearing infrastructure and organizational competence that didn’t

exist back then. FAANGs and service providers subsidized tooling and

infrastructure. The rest of the industry paid out of their own pocket

for the real-world projects where solutions were tested on the longer

tail of use cases and a generation of engineers were trained on

them. (Make your own estimates on what % of tech industry funding

may have gone to “break the monolith” projects alone.)

The positive side of the microservice bubble was that it socialized the

cost of maturing the technology. In 2025 we enjoy a collective knowledge

base of benefits, trade-offs, risks and, especially, contraindications

(knowing when not to use a technology is a good marker of maturity,

and it’s significant that only in the last couple of years it became

acceptable to say that a monolith is usually a better starting point).

The negative side was that, in retrospect, many organizations would have

preferred to opt-out of the battle testing part, and wait at the boring

side of the adoption curve.

The serverless trend may very well be directionally correct too. But a

technical decision maker considering to sponsor a migration will be

justifiably worried about miscalibrating that bet and underestimate the

pending cost to bridge the remaining maturity gap. With microservice

scars still fresh, and immersed in a

post-ZIRP

economic environment, this is already a risky proposition.

Where is the complexity of moving into serverless?

Load-bearing infrastructure

A naive mental model for the transition to serverless involves laying

each microservice in the chopping board and fragment its constituent

logical components into a collection of smaller functions. At a high

elevation this makes no fundamental change: a functional Lego block is

conceptually the same whether it’s implemented as an endpoint in a

microservice or a lambda function. But so are an electric and a

combustion car conceptually the same, at least until you’re trying to

refuel.

High-level abstractions are always supported by load-bearing

infrastructure which may (and should) be invisible, but is never

irrelevant. The transition to electric cars depends on adapting or

rebuilding the energy distribution network that is taken for granted in

combustion cars. The transition to microservices depended on providing a

new stack of technical infrastructure to solve distributed systems

problems that emerged as soon as communication between Lego blocks took

place over the network instead of a motherboard (to wit: on-wire

formats, latency, reliability, data integrity, service discovery,

deployment, observability, troubleshooting, etc.). In a similar way,

fragmenting a microservice into lambdas implies a leap away from a

significant part of of the previous load-bearing infrastructure.

A basic example are dependency injection frameworks like

Dagger, Google

Wire, Uber

FX, or Spring

Boot,

which simplify wiring up dependencies among the handful of internal

components that make up a typical microservice. After those components

fragment into a collection of lambdas, the scope expands from a narrow

problem of bookkeeping local references within a process, to one of

orchestrating cloud resources using raw cloud APIs.

Similar conversations appear in many other domains besides application

frameworks: observability, continuous delivery, etc. Piggybacking on

tooling and infrastructure for stateless architectures is insufficient

to support large serverless ones. Building purpose-specific abstractions

to fill those gaps makes for interesting engineering challenges, but any

decision maker considering a migration to serverless will rather see

them as an inconvenient liability, with uncertain cost, and with too

many odds of locking down engineering capacity that might be better used

for revenue-generating purposes.

Organizational readiness

Closing technical maturity gaps is not just a matter of building tools,

but also rewiring individuals and organizations to deploy them

effectively. Back in the 2010s, Netflix became one of the key referents

in applying microservices at scale in good part thanks to open sourcing

a vast portfolio of internal tools and

infrastructure. Their cloud architect at

the time, Adrian Cockcroft, said in a 2023 microservice

retrospective:

“maybe […] we came up with stuff and we shared it with people and a few

people took it home and tried to implement it before their organizations

were really ready for it.”

Most organizations have appetite for speed and growth. But introducing a

technical innovation that optimizes for scale, speed, and productivity

puts pressure on the organization to keep up and renegotiate trade-offs

around decision-making structures, communication dynamics, operational

capabilities, risk tolerance, quality standards, and similar factors to

stay aligned with the purely technical aspects.

In my experience, this organizational readiness has a significant lag

that manifests most often in delivery pipelines. Nowadays it’s easy to

find technical systems that look on the whiteboard like the canonical

fabric of independent, decentralized services on top of a bingo

card of modern tooling. But

behind the surface many conceal monolithic delivery processes where

supposedly autonomous teams are forced to parade changes in lockstep

through a byzantine, maintenance-heavy via crucis of ”dev”, “staging” or

“pre-prod” environments where broad test suites validate each change

against the entire system before it reaches production. This model has

obvious scalability problems that cancel most of the potential of

microservice architectures (and sometimes make things worse). But

getting the broader organization to buy into other ways of planning,

developing, testing, delivering and operating complex distributed

systems is tough.

Serverless amplifies the challenges of microservices

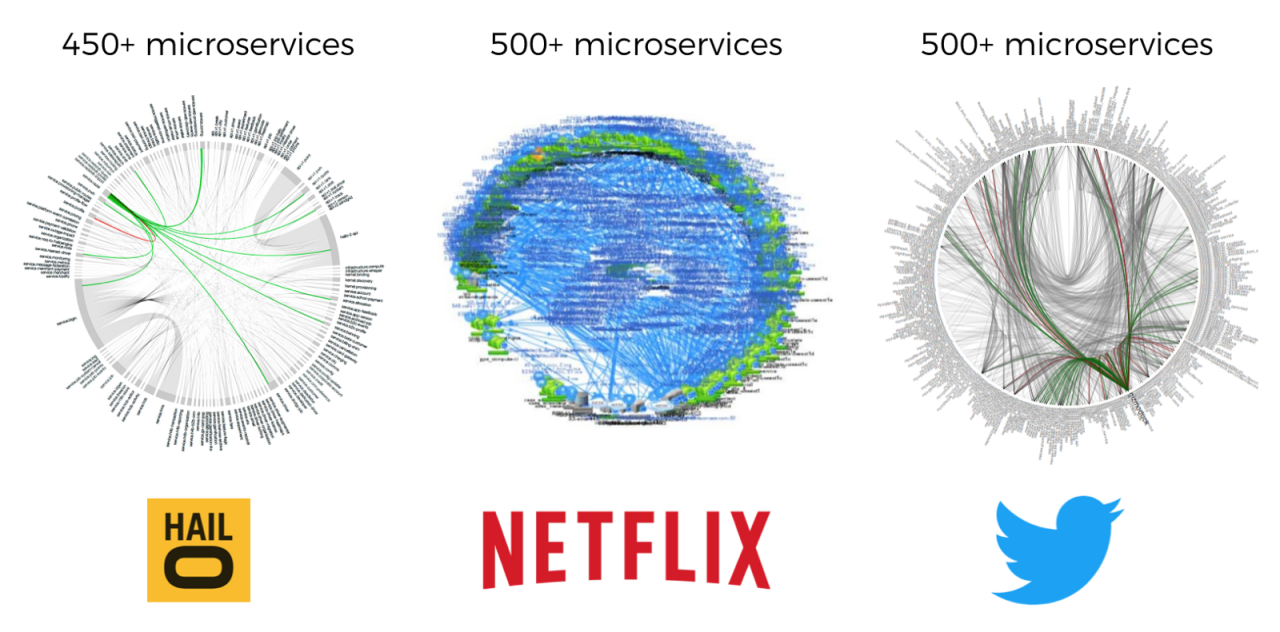

“Death Star” diagrams were commonly used in the early 2010s represent

the increased complexity inherent to microservice architectures. If

serverless implies that each one fragments further into hyper granular

lambda functions, then the application becomes a Death Star of Death

Stars, which is bound to exacerbate the same problems that the industry

has been grappling with for the past ~15 years. Technical ones might be

solved through sheer investment in tooling and infrastructure, but fewer

organizations are willing to take an unbounded share of that cost.

Rewiring individual and collective mental frameworks that can deploy and

operate them effectively will take much longer.

What are effective vectors for serverless adoption?

Head winds may mean that wholesale migration of workloads is unlikely to

happen in the short-medium term. This does not mean that serverless

lacks a solid value proposition (Simon Wardley has articulated the

case a

few

times), so it is still worth

finding adoption vectors that allow for selective, low-risk, incremental

steps. My blueprint is basically this:

- Focus on domains owned by fully autonomous teams, who are already

fluent in developing, deploying, testing operating all their software

independently from the rest of the rest of the organization, and where

product stakeholders are equally comfortable with that autonomy. - Migrate existing workloads that have well-scoped, self-contained

logic, don’t need complex state management, have low to mid-level

traffic and bursty profiles that fit well with cost / performance

trade-offs of serverless (that paragraph serves as a prompt into your

favourite LLM, which should spit out some combination of event-driven,

background tasks, glue for lightweight orchestration, user

authentication flows, etc.) - AI and LLM Integrations deserve their own category. As I mentioned

above, these pretty much satisfy all the above properties, tend to

appear in a more experimental context and drag less legacy

dependencies. With AI Agents shaping to be the trending topic of 2025,

the type of architecture described in Anthropic’s “Building effective

agents”

lends itself well to composites of small bits of business encapsulated

in functions.

I will close highlighting a central argument in Simon Wardley’s case for

serverless:

The future is worrying about things like capital flow through your

applications, where money is actually being spent and what functions,

monitoring that capital flow, tying it to the actual value you’re

creating […] All of a sudden, we’ve got billing by function, we can look

at capital flow in applications, we can associate value to the actual

cost.” (source)

To the extent that the main incentive for broad serverless adoption is

not technical, but financial, so the sponsor is unlikely to come from

the engineering department. This has non-trivial implications, but I’ll

leave that for another time.

Any thoughts? send me an email!