Science Tips Tips Tricks Technology Aerojet Rocketdyne expands operations to deliver four SLS engines a year

Science Tips Tips Tricks Technology

NASA is extending its RS-25 engine production contract with Aerojet Rocketdyne through the rest of the decade, a move that guarantees a steady supply of liquid-fueled engines for the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket’s core stage.

This consolidates Aerojet Rocketdyne’s RS-25 engine contracts, ensuring they continue to prepare the 16 RS-25 flight engines inherited from the Space Shuttle Program for the first four SLS missions while now producing four new engines a year — 24 total — by the end of 2029 to support SLS flights until at least 2030.

Production restart contract extended through the 2020s

Sixteen flight and two ground test RS-25 engines were inherited by SLS from the Space Shuttle Program, and Aerojet Rocketdyne provided the engineering support to adapt and recertify the existing reusable engines to fly on the expendable SLS with a new engine controller.

The company was subsequently contracted in 2015 to restart production of new flight engines that would be needed beginning with the fifth SLS launch.

Along with re-establishing its supply chain, Aerojet Rocketdyne also modernized manufacturing methods for several of the engine components with the goal of reducing the cost of production while maintaining its reliability.

The RS-25 production restart contract was originally awarded in late 2015 for “six new R-25 engines.” Now, the extended contract “…brings the total contract value to almost $3.5 billion with a period of performance through Sept. 30, 2029, and a total of 24 engines to support as many as six additional SLS flights,” NASA said in a May 1 news release.

Aerojet Rocketdyne is the prime contractor for RS-25; with the initial “adaptation” contract period expiring at the end of March 2020, almost all RS-25 work is now consolidated under the production restart contract. “The contract includes a lot of scope beyond just buying and fabricating parts and assembling them into an engine,” Jim Maser, Senior Vice President of Aerojet Rocketdyne’s Space Business Unit, said in a May 5 interview.

“We have flight support in there, vehicle integration, special test equipment, property management, data management, the full financial and technical reporting that goes along with a NASA human spaceflight contract, and of course the mission assurance activities that go along with that, too, to provide the level of insight and oversight that NASA needs to be sure that when their astronauts are flying under the power of our engines that they’re flying safely.”

Aerojet Rocketdyne spokesperson Mary Engola said that no more work is being performed under the adaptation contract and that closeout of the contract should take place in May. With the addition of eighteen more engines to the production restart contract, Maser said the company has begun buying the long lead materials for them.

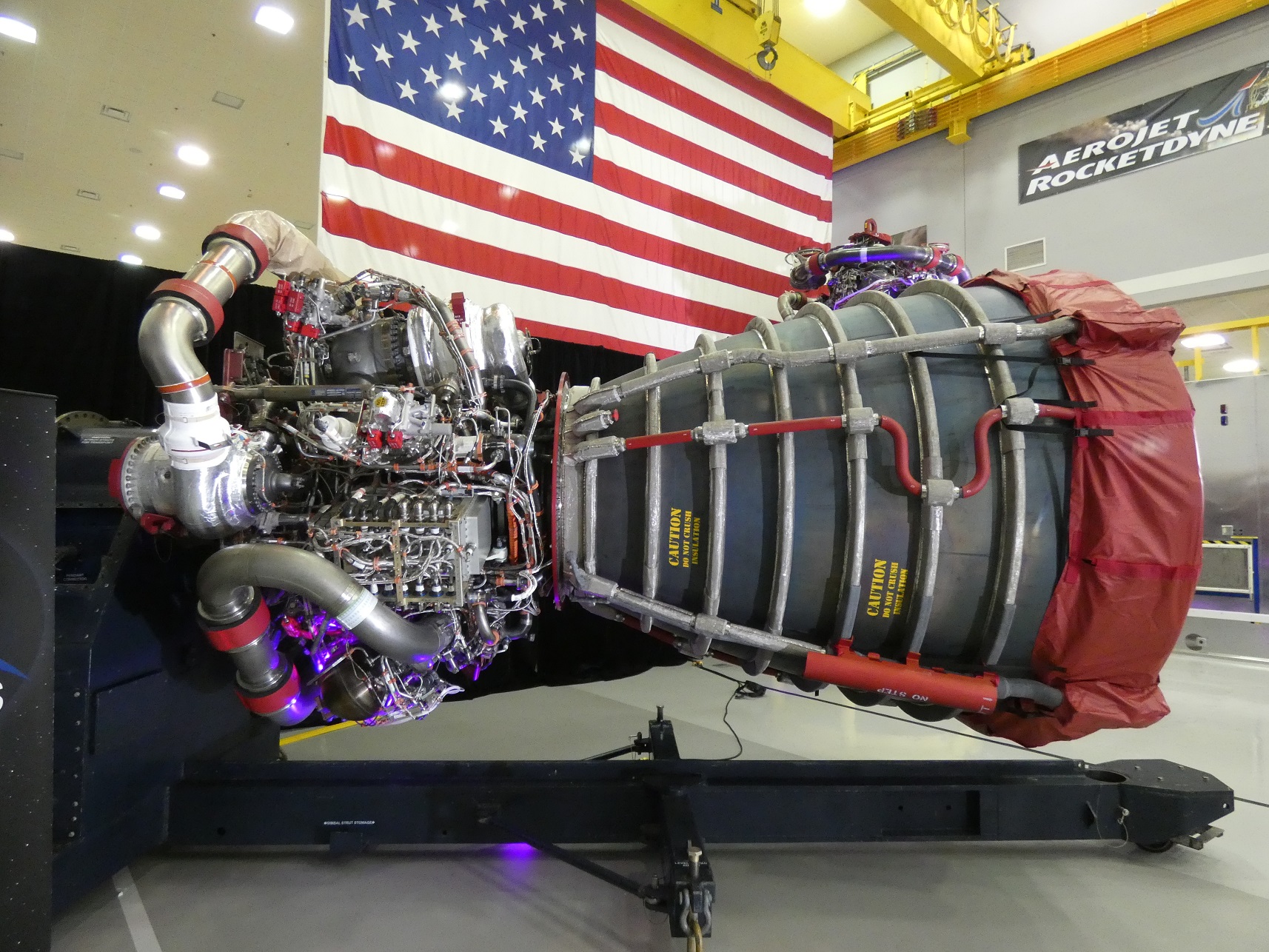

RS-25 engine 2063 on display at Stennis Space Center in February. Credit: Philip Sloss for NSF.

The company’s Canoga Park facility in the Los Angeles metro area builds and assembles most of the engine components, with turbopump components being built in West Palm Beach, Florida. The components are shipped to Stennis Space Center for final assembly and acceptance testing before delivery for Core Stage installation.

“Under our contract, we’re building certification [components] because we’re basically restarting the line,” Maser said on May 5. “We hadn’t really built these engines for about fifteen years and there will be six production engines out of that and a number of certification engines.”

Engola noted that production of some SSME spares ended in 2010, but the last bulk production of major components was about two decades ago. “SSMEs were being manufactured in our facility on Canoga Avenue in Canoga Park, and we’ve since closed that facility down and consolidated our operations into our DeSoto facility and stood up the manufacturing for RS-25 in that facility,” Maser said.

“Aerojet Rocketdyne has overall about five-thousand employees and not everybody works on the RS-25 full time necessarily, but in general we’ve probably got around seven hundred, plus or minus, people working on it right now.”

Initial sets of new engine component hardware are being retrofitted to the two existing ground-test SSMEs inherited from Shuttle, development engines 0525 and 0528. Engine 0528 will now be known as Retrofit 2 and 0525 will be Retrofit 3.

The first full, new build engine will be a ground test unit for production restart – called a certification engine – and will bring in the first new production powerhead.

“It is very typical in aerospace if you were to change suppliers or be out of production for any period of time when you start back up you have to recertify that you can actually build these engines,” Maser noted. “Today we have some new suppliers, we’ve modified the design a little bit and we’re doing that [now] and so the eighteen engines [modifications] are ideally a follow-on production for a stable configuration.”

Final assembly of the certification engine is planned at Stennis in the second half of 2021.

Following the upcoming Retrofit 2 and Retrofit 3 test series using existing hardware, the new test engine could begin the final certification set of tests in the first quarter of 2022. Design Certification Review (DCR) would then occur later in 2022, and the delivery of the first new flight engine would follow in 2023.

The goal with the initial six flight engine production run reduces the cost of building an engine by thirty percent.

While they reconnect with parts and material suppliers and re-establish engine component manufacturing for new engines, Aerojet Rocketdyne also continues to support ongoing SLS first flight development activities. The first four flight SSMEs planned for use with SLS are installed in Core Stage-1 ahead of major Green Run testing at Stennis.

Aside from the new engine controller, the engines are more or less the same hardware that last flew in Space Shuttle Orbiters nine years ago; however, SLS has a different operating environment outside the Shuttle envelope and the earlier contract certified that the Shuttle engines were adaptable to SLS.

Along with ongoing hardware maintenance on the engines to support time and cycle requirements, Aerojet Rocketdyne will provide engineering support at multiple sites as the first Core Stage is test-fired on the ground at Stennis and then in the processing lead up at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) for launch.

Credit: Aerojet Rocketdyne.

(Photo Caption: The first production restart main combustion chamber (MCC) is received at Aerojet Rocketdyne’s Stennis facility in April, 2018. The MCC was retrofitted to Shuttle-era ground test engine 0525 for the Retrofit 1b test series that was completed in February, 2019. The initial production runs of engine components are being retrofitted to the existing ground test engines, replacing nearly everything except the engine powerhead.)

“So far [at Green Run] it’s not very intensive,” Maser noted, but Green Run work at Stennis was halted in mid-March by the COVID-19 pandemic. They will become more involved with pre-firing engine checkouts, the Wet Dress Rehearsal, the hot-fire test, and post-firing refurbishment. “We’re still working out what the exact post-Green Run activity is at Stennis and what would be at KSC as part of initial launch processing.”

Engola noted that Green Run console support and touch labor are performed under a contract with Core Stage prime contractor Boeing, but overall engineering support is a part of the production restart contract that was extended last week.

Expanding factory capacity to deliver four engines per year

NASA’s current goal for SLS flight rate is once per year. The initial production restart contract established a delivery rate of two engines per year for the first six engines, but the contract modification looks to reach the annual flight cadence that would require four engines.

Fernando Vivero, Aerojet Rocketdyne Los Angeles Site Lead, noted in February that the company spent $57 million developing plans on to expand production at Canoga Park, looking at purchasing additional equipment and increasing floor space. The additional award in the contract modification allows them to begin executing that plan.

[The facility] right now is set up for two per year and we’re actually expanding with this contract to build four engines a year,” Maser noted. “We’d actually moved out on risk before we even signed the contract, so we did some work last year.”

“We’ve been a little slowed down with the COVID-19 activity but this is a very heavy spending year for us in terms of converting a floor in one building to take some of our smaller machines and then expanding our facility to have a little bit bigger footprint to be able to handle the amount of work and process we’ll be having with four engines per year.”

“These nozzles are pretty big and so we need space to move them around in and store them as they’re getting ready for their next operation and actually to operate upon multiple nozzles at a time,” he added. “We’re in the middle of that expansion right now and we’ll complete it by next year.”

“In the meantime, we’re working hard to bring in some of the long lead material and start machining or fabricating of the subcomponent detail level already.”

Credit: NASA/Jude Guidry.

(Photo Caption: The four former SSMEs, now RS-25s, assigned to Core Stage-1 at the time of initial installation in the stage’s engine section/boattail last November at the Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF). Each Core needs four engines and Aerojet Rocketdyne is now contracted to expand production to deliver a full set to MAF annually for installation.)

Studies are also looking at future options to further increase the production rate. “We’ve definitely studied going from four engines per year to six per year to eight per year,” Maser said.

“We’ve laid that out and we’ve started looking at it in more detail because that would require some additional expansion and we have to talk to suppliers. We’re getting our arms around any expansions that they would have to do. We’re also simultaneously looking at one more post-eighteen engine [order] design change for the nozzle and also for what we call the powerhead which is what supports all the turbomachinery.”

“We have to do some technology development for some lower cost options for those that would not only reduce the cost but reduce the cycle time for building those,” he added. “Right now it takes a little over four years to build an engine and if we could implement some design changes to the nozzle and the powerhead we could take that down to three years, which then allows us to be more efficient with the space we have and also more cost-effective.”

“These design changes we’re studying and we’re working with NASA on, particularly the nozzle and the powerhead, that would take that thirty percent to fifty percent [production cost] reduction overall. So the next step is four per year and we are actively studying six and eight per year.”

Supporting return to Stennis when NASA is ready

The main focus of the Green Run at Stennis is on the Core Stage itself, but NASA and Aerojet Rocketdyne were also preparing to resume single-engine production restart testing before the center was shut down in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. “We have not gotten back in, they’re still on Stage 4,” Maser said. “As soon as NASA feels it’s safe, we’re going to bring our people back in but it’s a NASA site so we’re following their coronavirus stage approach to that.”

“In the meantime, a lot of the people that are not in working have actually been able to do a fair amount of training online that they would normally have to do during the year so we’re helping them be productive that way but we’re anxious to get back in.”

“We have our own isolated building, so we still have people working on RS-68 down there,” he noted. “Across all of our sites it’s been a learning experience but we’ve implemented a lot of safety protocols at Stennis, so we do daily temperature, thermal scanning, touchless thermal scanning, mandatory masks, a lot of extra cleaning, that sort of thing, and we’re setting up the work environment such that people can maintain social distancing also.”

Credit: Philip Sloss for NSF.

(Photo Caption: The A-1 Test Stand under refurbishment at Stennis Space Center on February 10. The propellant run-tanks were bagged for corrosion removal and repainting, one of the renovation projects going on in preparation for resuming single-engine RS-25 testing. Work was halted in March due to the COVID-19 stand down and NASA is still assessing options for the workforce to return to the center.)

“When NASA feels it’s safe to bring people back in we’re ready to go. We’re ready to get them back to work and we know we can do it safely.”

Work also continues on production of new engine components at Canoga Park. “Once again it was a learning experience but we do have multiple shifts to try and divide people up, we’ve gone to even shifts in the break room, that sort of thing with cleaning in between,” Maser explained.

“We went to mandatory masks in the shop quite a while ago. We’re doing thermal scanning, not every one every day but we try and get everyone at least once a week and so far it’s going pretty well.”

“We’ve only got a month to six weeks worth of data, but we’re not seeing a lot of inefficiency,” he added. “Work is progressing relatively well, it’s progressing safely, and I think people feel it’s a safe environment.”

“In the office environment we’re also requiring masks and social distancing and we’re looking at what would be a slow, phased return plan depending on what local communities do. Right now at least for the Space Business Unit we’ve got about I’d say sixty to seventy percent of our people working from home and then the remainder are mostly in to support the factory environment to continue building hardware.”

Lead image credit: NASA.