Four Hidden Species of Portuguese man-o’-war — Crooked Timber

There’s been a a certain amount of negativity floating around lately. So, let’s talk about a toxic, venomous freak of nature and the parasite that afflicts it.

Biology warning, this gets slightly squicky.

Let’s start with the toxic, venomous freak of nature: the Portuguese man-o’-war.

If you’ve spent a lot of time in warm ocean waters, you’ve probably encountered one of these guys. They’re hard to miss! They come in a variety of colors — pink, blue, purple — and they’re pretty prominent, floating on the surface of the ocean like discarded party balloons. And if you’ve ever been stung by one, well, you probably remember that. Their stings aren’t lethal to humans, but they’re welt-inducing and painful.

So it’s a jellyfish. Except it isn’t really: it’s several jellyfish, smooshed together. And here’s where the “freak of nature” part kicks in.

I mean, yeah, strictly speaking nature has no freaks; every species that exists, belongs; everything is a product of evolution and Life’s Rich Pageant, yadda yadda. But the Portuguese man-o’-war — Physalia physalis, for you biologists — is honestly kinda freaky. Because Physalia is a colonial organism.

What this means: a single Portuguese man-o’-war is composed of four or five separate animals. (We’re not actually sure how many.) One animal is the balloon-sail-thingy on top; another is the stinging tentacles; another is the digestive system; another is the gonads. And they’re completely distinct organisms.

How this happens: when a Physalia egg is fertilized, it starts dividing, like every other fertilized egg. But pretty quickly it breaks apart into two and then more distinct embryos — genetically identical, but physically separate. And those embryos develop into completely different creatures. Then, later in development, those creatures re-attach to form a single Frankenstein organism. The various parts have their own nervous systems, which don’t seem to connect.

Here’s an analogy: imagine that before birth, you are identical twins. But instead of growing into two babies, one twin grows into a bodiless head, the other into a headless body. Then just before birth they stick together, but they don’t actually merge back into one. No, going forward you are a bodiless head glued on top of a headless body, ever after. It’s kind of like that.

Axe Cop copyright Ethan Nicolle, 2017. — Look, I said it was going to get a bit squicky.

Now, colonial animals aren’t unknown in nature. But most of them are either dinky (Volvox, don’t ask) or they’re big, but it’s basically cut-and-pasting the same creatures over and over. So, some corals are colonial, but all this means is that the individual polyps have grown into each other to produce a sort of living carpet interlaced through their stony skeleton. But the man-o’-war is a respectably large animal — they can grow as big as a large house cat — and so are its colonial components. And the components are extremely specialized: the float-animal part of it looks and acts nothing like the tentacle-animal part.

Physalia is by far the largest complex colonial animal. And — this bit is odd — it doesn’t have any relatives. It’s the only genus in its family. Put another way, within the jellyfish it has no siblings and only a few very distant cousins. (One of which is the ridiculous creature known as the Flying Spaghetti Monster Jellyfish, but never mind that now.) It’s a very successful organism! There are millions and millions of them, found all over the world in tropical and subtropical oceans. So you would expect to see speciation, different relatives — big ones, little ones, a bunch of variations on a theme. More on this shortly.

But meanwhile, the whole “colonial animal” thing looks like evolution’s first attempt to figure out, you know, organs. I mean, the first multicellular animals were probably sponges, and sponges don’t actually have organs. But more complex animals have distinct and differentiated organs, modules of specialized tissue performing particular functions, because those turn out to be super useful. Physalia and other colonial animals look like a beta-test platform for this new “organ” technology. Most of the animal kingdom moved on to “oh wait, why don’t we just have one single creature that grows the different modules inside it”, but a few colonial animals stuck with Plan A and made it work.

Okay, so that’s the “freak of nature” part. What about the “toxic and venomous”? Well, as every good science nerd knows, toxic and venomous are two different things. “Toxic” is something that, if you eat it or just lick it or touch it, you get poisoned. Nightshade is a toxic plant; those brightly colored South American tree frogs are toxic animals. “Venomous” is something that delivers poison with a bite or sting, like a snake or a wasp. Most poisonous animals are either one or the other.

But not the man-o’-war! It is of course highly venomous. It has stinging tentacles that can drift for many yards behind it.

The toxic sting is painful to humans. To fish, it causes paralysis. And once the fish is paralyzed… well…

“The nematocyst delivers a toxin that results in… general paralysis, affecting the nervous system and respiratory centers, and results in death at high doses. Once a tentacle comes into contact with its prey, the prey is carried up towards the gastrozooids near the base of the float. The gastrozooids respond immediately to the capture of prey, and begin writhing and opening their mouths. Many gastrozooids attach themselves to the prey – upwards of 50 gastrozooids have been observed to completely cover a 10 cm fish with their mouths spread out across the surface of the fish. The gastrozooids release proteolytic enzymes to digest the fish extracellularly, and are also responsible for intracellular digestion of particulate matter. The digested food products are released into the main gastric cavity for uptake by the rest of the colony.”

Got that? The “gastrozooids” are short plump tentacles with mouths at the end, the many mouths of the stomach-animal. They release enzymes that dissolve the fish into a nutritious slurry, which they then drink. The fish may or may not be alive at the beginning of this process. It is definitely not alive by the end. And all of the different colony animals connect to the gastric cavity, so they can all absorb nutrition from it: the stomach-animal predigests the food for everyone else.

Okay objectively it’s no worse than a lion biting into an antelope but, not gonna lie, this is some H.P. Lovecraft stuff right here. — But okay! That covers the “venomous”. What about the “toxic”? Are they poisonous to eat?

Ha ha, no, that would be too simple. The Portuguese man-o’-war is poisonous to breathe. It inflates its balloon-sail by using an enzyme to produce gas from its food. And the gas it produces? Carbon monoxide. Fully inflated, the bell contains a mixture of normal air and deadly gas. So if you grabbed one, bit into the balloon and then huffed it… Well, there probably wouldn’t be enough monoxide to kill you dead on the spot, but you’d probably get sick and you might pass out. So I think that counts as “toxic” by any reasonable standard.

And why does it use carbon monoxide? This is “imperfectly understood”.

And it’s not the only thing we don’t know. For instance, there’s its reproduction. These guys are either male or female, and they have gonads. But they don’t have sex in any way we’d recognize. Instead, every so often their gonads bud off things called gonodendra, which are… mobile gonads. The gonodendra break off and swim away. And what happens then?

“As larval development has not been observed directly, everything that is known about the early stages of this species is known from fixed specimens collected in trawl samples. Gonodendra are thought to be detached by the colony once they are fully mature, and the nectophores may be used to propel the gonodendron through the water column. Released mature gonodendra have not been observed, and it is not clear what depth range they occupy. It is also not known how the gonodendra from different colonies occupy a similar space for fertilization, or if there is any seasonality or periodicity to sexual reproduction. Embryonic and larval development also occurs at an unknown depth below the ocean surface. After the float reaches a sufficient size, the juvenile P. physalis is able to float on the ocean surface.”

— Yeah, there’s a lot of “is not clear” and “is not known” here. You might think that an animal that is well-known, conspicuous, weird, and has potential economic impact (they’re considered bad for certain fisheries) would be better studied. It isn’t. I’ve been searching and the man-o’-war gets on average less than one published paper per year. For something so interesting, it’s not much.

(And yeah, the detachable free-swimming gonads. Do they swim around until they find gonads of the opposite sex? How exactly…? And then do they…? So many questions!)

Which brings me to this paper, the topic of this article. You remember how, several paragraphs back, I noted that the man-o’-war seemed to be a weirdly isolated species? Well, last year a bunch of marine biologists at Yale decided to test that. So they collected specimens from all over the world and ran DNA tests on them. And, lo and behold: they found that there were actually five species of Physalia. We didn’t realize it because they all kinda look alike (to us, anyway). I asked earlier why we weren’t seeing speciation. It turns out we are. It’s just very subtle and non-obvious and we had to look hard.

This wouldn’t be so weird if it was, like, one species per ocean. But it’s not. There’s one North Atlantic species, but there are four species in the Pacific, and one of them is in the South Atlantic too.

The technical term for this is “cryptic diversity”. It happens a lot, especially with species that aren’t well studied. It’s biology, yeah? Look closely, and everything turns out to be more complicated.

So now a mystery has been replaced by a different mystery: why are there five species (at least) of Physalia? The open ocean is a big place, but it’s flat and there are no barriers. The Portuguese man-o’-war sails around all over the place — it’s pretty darn mobile for a jellyfish. You’d expect populations to keep mixing. So, why have they split into different species? Subtle differences in water composition, temperature or salinity? Populations kept apart by wind and currents? Different mixes of predators and prey? And if they’ve split into different species, why do the various species still look and act so alike? Right now we have no idea.

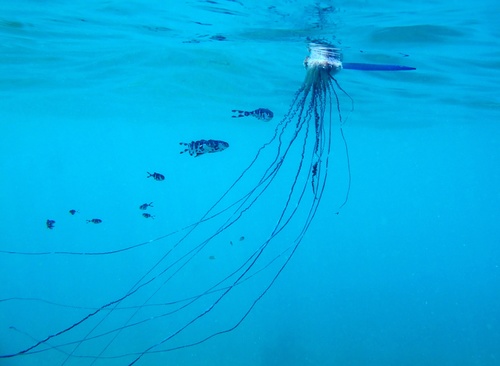

And speaking of mysteries, if you find a Portuguese man-o’-war, good chance you may find one of these guys too:

This is Nomeus gronovii, the bluebottle fish. And it’s a parasite on the Portuguese man-o’-war.

You know clownfish, and how they can live in the stinging tentacles of a sea anemone, because they’re immune? And they’re symbiotes — the anemone protects them, they share their meals? Well, this is like that, except it’s not. The bluebottle lives among the tentacles, but it’s not a symbiote. It eats the tentacles. In particular, it snacks on newly sprouted young tentacles, probably because they don’t have as many stinging cells yet. And when it feels the need for something a little more solid, it also will bite chunks out of the man-o’-war’s gonads. Even granting that the man-o’-war regularly grows new gonads, biting off your host’s junk is not the behavior of a welcome guest.

Oh, and: unlike the clownfish, the bluebottle is not immune to its host’s stings. It has limited resistance — it can tank a sting or two — but if it gets stung too many times in rapid succession, it will be paralyzed and eaten.

(This raises an interesting question: why is it not immune? We know that clownfish can evolve immunity to the stings of the anemone. So why not the bluebottle? Well, this is pure speculation, but my guess would be that it’s because the bluebottle is a parasite rather than a symbiote. So there’s probably an evolutionary arms race: the man-o’-war keeps evolving new venoms that can kill the bluebottle, and the bluebottle only has time to evolve limited resistance before the man-o’-war shifts venoms again.)

The bluebottle survives among the tentacles by being small and very nimble. It has actually evolved extra vertebrae so that it can twist and weave better! But at some point, it simply grows too big. So, only juvenile bluebottles live as parasites. When they reach a certain size, they swim off and… uhh, we’re not sure, actually. They seem to be demersal (bottom dwellers) because they turn up in trawl nets sometimes. But how they live, how they mate, what they eat and what eats them… we have only the vaguest idea. As far as I can tell, the last paper specifically studying Nomeus gronovii came out in 1983. Nobody seems to be working on this right now.

Just a few days ago, my CT colleague Kevin noted that there are more crap academic papers out there than ever. I’m not an academic, but yeah, that sounds legit. But at the same time, there are so many good papers out there waiting to be written! There’s so much we still don’t know! Water, water everywhere, and not a drop to drink!

But anyway. We knew these guys were wind-sailing, carbon monoxide powered, venomous colony creatures with clusters of squirming mouth-tentacles and detachable gonads. But it turns out they were hiding even more complexity and mystery.

I just think that’s cool. If you’ve read this far, I hope you agree.